While I was on vacation, a small (8-line) Denoland changeset caught my attention. The changeset improved HTTP performance by about 10% simply by wrapping a stream in a Box. This led to all sorts of questions from me, so I decided to dive down the rabbit hole.

Memory

Like many programming languages, memory in Rust is divided into two primary regions: the stack and the heap. The stack memory is where local variables, function arguments, and return values are stored. The stack is continually pushed to and popped from as functions are called and returned from. The heap is used for dynamic memory allocation, storing objects and data structures that require a longer lifespan.

In Rust, you typically wrap your data structures in a Box to allocate them on the heap; otherwise, they will be allocated on the stack.

Historically, it was common to allocate large structures on the heap and only pass pointers to this data. This helped ensure that copies of the data were not being performed each time a function was called. However, with modern compilers and Rust’s strict memory guidelines, the optimizer can usually remove unneeded copies, so focusing on the performance of heap-based vs. stack-based allocations is not something most developers should concern themselves with.

Questions

The Deno change-set moved a large data structure onto the heap to avoid memory copies. This made sense, but led to a number of questions:

- Could I identify the generated code that led to these excessive memory copies?

- Could I reproduce this for a small example and see just how slow these memory copies really were?

- Is this something we should consider each time we have a large data structure, or will the Rust compiler typically do the right thing?

LLVM IR

To answer the first question, we need to understand the code that Rust generates.

The Rust compiler targets the LLVM Intermediate Representation (LLVM IR). What this means is that instead of generating machine code for every target Rust supports, the compiler generates IR, and LLVM can then generate highly optimized machine code for each platform. Miguel has written a great Gentle Introduction to LLVM IR.

While the LLVM IR isn’t typically meant to be read by humans, the syntax is actually pretty easy to follow, and if you have some experience with assembly code, LLVM IR isn’t that complicated.

To generate the LLVM IR, you can use the --emit=llvm-ir flag. Specifically, I checked out the Deno codebase, moved to the ext/http directory, and ran:

cargo rustc --lib -- --emit=llvm-irI did this for both commit 5c54dc and 930ccf, the commit that included the fix and the one before.

Before the fix was committed, the IR showed a memory copy of 5624 bytes before a deref_mut was invoked. This copy of 5K bytes each time this code path was hit would add up quickly.

bb5: ; preds = %bb3

store i8 0, ptr %_13, align 1, !dbg !392622

store i8 1, ptr %_12, align 1, !dbg !392622

call void @llvm.memcpy.p0.p0.i64(ptr align 8 %_9, ptr align 8 %response_body, i64 5624, i1 false), !dbg !392622

; invoke <core::cell::RefMut<T> as core::ops::deref::DerefMut>::deref_mutAfter the fix was applied, the amount of memory copied was a more reasonable 48 bytes.

bb5: ; preds = %bb3

store i8 0, ptr %_13, align 1, !dbg !392963

store i8 1, ptr %_12, align 1, !dbg !392963

call void @llvm.memcpy.p0.p0.i64(ptr align 8 %_9, ptr align 8 %response_body, i64 48, i1 false), !dbg !392963

; invoke <core::cell::RefMut<T> as core::ops::deref::DerefMut>::deref_mutFor details about the memcpy intrinsic, please refer to the llvm documentation.

Reproducibility

This was clearly a problem for the Deno project, but is this a problem in general? More specifically, could I reproduce this problem with a simple example and see a measurable difference when passing around a 5KB data structure?

I built a small Rust program with a 5KB data structure and recursively called a function 200 times. During the last call, I summed up all the values in the data structure. I repeated this experiment 50,000 times.

use std::time::Instant;

struct Data {

content: [u32; 1250],

_extra: [u32; 10], // Used avoid purely register based allocations

}

fn sum_for_fun(data: Data, depth: u32) -> u32 {

let depth = depth + 1;

if depth < 200 {

return sum_for_fun(data, depth);

}

data.content.iter().fold(0, |acc, e| acc + e)

}

fn main() {

let start_time = Instant::now();

for _ in 1..50000 {

let d = Data {

content: [0; 1250],

_extra: [0; 10],

};

sum_for_fun(d, 0);

}

let duration = start_time.elapsed();

println!("Duration {:?}", duration);

}Because I was sure the compiler could optimize this copy away, I generated the LLVM IR with optimization level 0 and emitted the IR.

rustc snippet.rs -Z mir-opt-level=0 --emit=llvm-ir --edition=2021We also added a small (40-byte) extra allocation, as the compiler was able to store the entire data structure using registers, especially when we started to move things into a Box. But we can see that each time the sum_for_fun function was invoked, a memcpy of 5040 bytes was performed.

bb2: ; preds = %bb1

call void @llvm.memcpy.p0.p0.i64(ptr align 4 %_10, ptr align 4 %data, i64 5040, i1 false)

; call no_box::sum_for_fun

%3 = call i32 @_ZN6no_box11sum_for_fun17hee4b4f97b8efe937E(ptr align 4 %_10, i32 %_5.0)

store i32 %3, ptr %_0, align 4

br label %bb7Moving the content into a Box, and repeating the experiment, the memory copy dropped to a reasonable 48-bytes.

struct Data {

content: Box<[u32; 1250]>,

_extra: [u32; 10], // Used avoid purely register based allocations

}bb2: ; preds = %bb1

store i8 0, ptr %_17, align 1

call void @llvm.memcpy.p0.p0.i64(ptr align 8 %_10, ptr align 8 %data, i64 48, i1 false)

; invoke no_box::sum_for_fun

%9 = invoke i32 @_ZN6no_box11sum_for_fun17hee4b4f97b8efe937E(ptr align 8 %_10, i32 %_5.0)

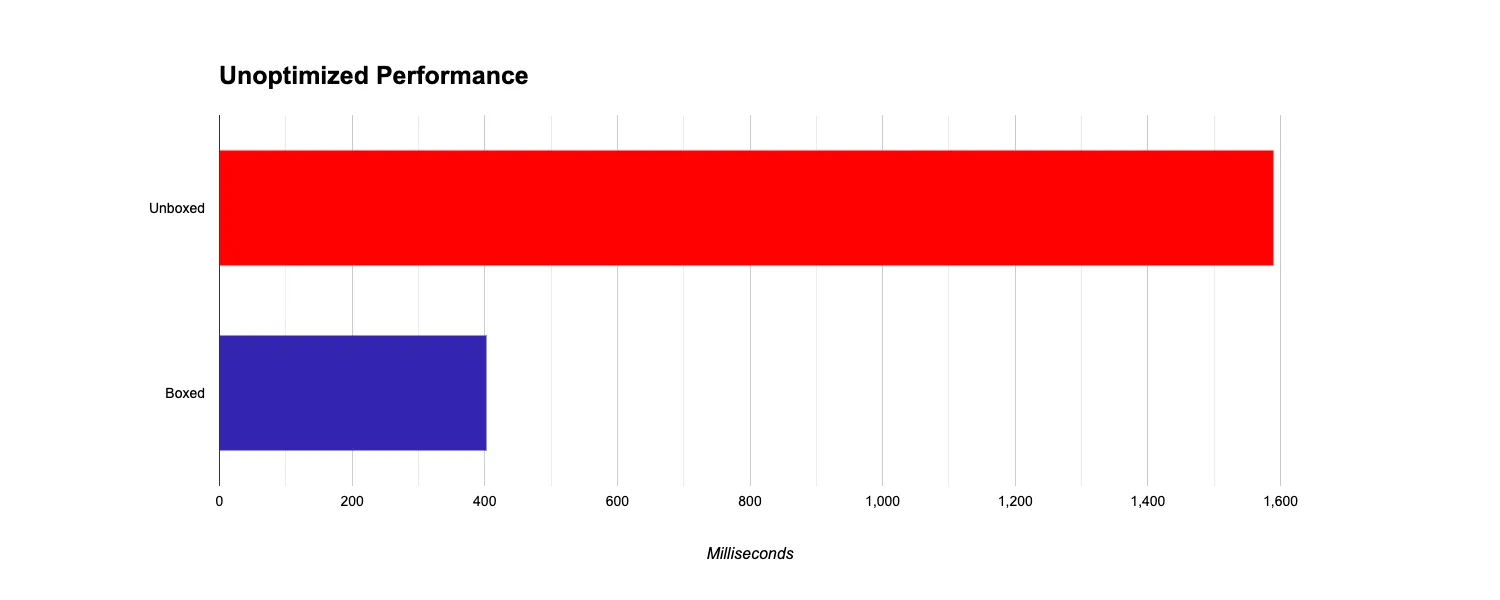

to label %bb3 unwind label %cleanupIn terms of runtime, the unoptimized boxed version of this code ran in 401.65ms, while the unoptimized unboxed version took 1.59s. That’s over 3x longer.

However, if we run the Rust optimizer, then the boxed vs unboxed versions are almost identical, taking about 400ms each. Trust your optimizer, kids.

Optimizations

In most cases, the optimizer is smarter than the developer. In the example above, both the boxed (heap-based) and unboxed (stack-based) versions run in the same amount of time if compiler optimizations are enabled. Looking at the LLVM IR when optimizations are enabled, no memory copying is performed on this structure during the recursive calls.

In the case of the Deno example, things are a bit more complicated than in my simple example. The Deno structures are often used across FFI bridges, and this particular struct uses Structural Pinning. It’s not clear exactly why the optimizer could not remove the memory copies for this structure, but the Deno team did the right thing by measuring the performance of their specific use case and optimizing accordingly. Never take anything for granted, kids.

Release

Finally, I compiled the code with the --release flag. The results were around 6ms for the unboxed version and 5ms for the boxed one—although the variance in each run was pretty high. While I was aware that the --release flag performs additional optimizations, I was surprised by just how much faster the final code was. One of the biggest improvements in the LLVM IR with the --release flag is the removal of panic_const_add_overflow whenever arithmetic operations are performed. Release your software, kids.

Lessons Learned

A few days off and an interesting eight-line code change led me down a rabbit hole I didn’t expect to fall into. I learned a lot about how Rust generates LLVM IR and how different optimization levels affect the generated code. I also saw firsthand how a large data structure can result in unnecessary memory copies.

While I was able to reproduce a simple example that exhibited the same behaviour as the Deno codebase, I was unable to reproduce the example when compiler optimizations were enabled. This led to a few lessons learned:

- Trust the Optimizer: Trust the Rust compiler to optimize your code. Focus on correctness before performance, as the optimizer will usually do the right thing.

- Don’t Blindly Trust the Optimizer: While the optimizer is generally better than you, if you notice something suspicious, measure its impact and be prepared to make changes accordingly. In this example, the Deno team noticed a significant amount of time spent in

memcpyand addressed the issue by moving the large data structure onto the heap. - Run Your Code in

--releaseMode: I knew--releasemode was fast, but I didn’t realize it was 100 times faster. Make sure you are always releasing.